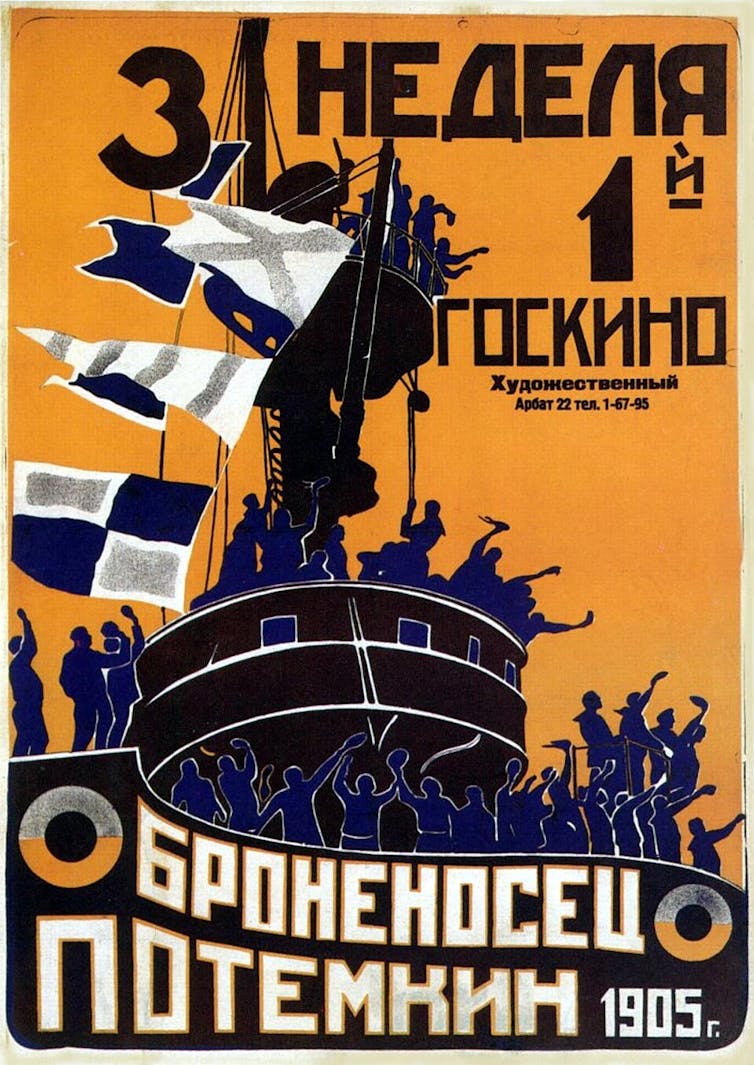

A landmark film in Russian cinema, Sergei Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin may have first been shown in Moscow on December 24 1925, but its enduring appeal and relevance are evident in the many homages paid by film-makers in the century that followed. So what made this film, known for its cavalier treatment of historical events, one of the most influential historical films ever made?

Britannica / Wikipedia

The story of the making of the film provides some answers. Following the success of his 1924 debut Strike, Eisenstein was commissioned in March 1925 to make a film that would mark the 20th anniversary of Russia’s revolution in 1905. This widespread popular uprising was triggered by poor working conditions and social discontent swept through the Russian Empire, posing a challenge to imperial autocracy. The attempt failed but the memory lived on.

Originally titled The Year 1905, Eisenstein’s film was envisaged as part of a nationwide cycle of commemorative public events across the Soviet Union. The aim was to integrate the progressive parts of Russian history before the 1917 Revolution – in which the general strike of 1905 assumed central place – into the fabric of the new Soviet life afterwards.

The original screenplay envisioned the film as the dramatisation of ten notable, but unrelated, historical episodes from 1905: the Bloody Sunday massacre, the antisemitic pogroms and the mutiny on the imperial battleship Prince Potemkin, among others.

Filming the mutiny, recreating the history

The principal photography started in summer 1925, but yielded little success, after which the increasingly frustrated Eisenstein moved the crew to the southern port of Odessa. He decided to drop the loose episodic structure of the script and refocus the film on just one episode.

The new screenplay was solely based on the events of June 1905, when the sailors on the battleship Prince Potemkin, at the time docked near Odessa, rebelled against their officers after they were ordered to eat rotten meat infested with maggots.

The mutiny and the follow-up events in Odessa were now to be dramatised in five acts. The opening two acts and the closing fifth corresponded to the historical events: the sailors’ rebellion and their successful escape through the squadron of loyalist ships, respectively.

The two central parts of the film, which describe the solidarity of the people of Odessa with the mutineers, were written anew and were only loosely based on historical events. Curiously, over the century of the film’s reception, its reputation as a quintessential historical narrative rests mainly on these two acts. What accounts for that paradox?

Wikipedia

The answer may lie in the central two episodes, particularly the fourth, with its poignant depiction of a massacre against unarmed civilians – including the famous scene of a baby in a runaway pram, bouncing down the steps – that imbue the film with powerful emotional resonance and grant it a sense of