BELEM, Brazil — Maria Gorete, who just began ranching three years ago, is doing something new with her 76 head of cattle in the Brazilian countryside near the town of Novo Repartimento.

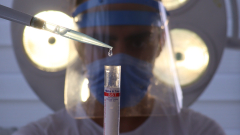

She’s piercing their ears.

Their new jewelry — ear tags, actually — will track their movements throughout their lives as part of an initiative aimed at slowing deforestation in the Brazilian state of Para. Depending on how well it works, it’s the kind of solution the world needs more of to slow climate change, the subject of annual United Nations talks just a few hours away in Belem.

With about 20 million cattle in Para, it’s a mammoth task. Some of them are on big farms closer to cities, but others are in remote areas where farmers have been cutting down Amazon rainforest to make room for their pastures. That’s a problem for climate change because it means trees that absorb pollution are being replaced by cattle that emit methane, a powerful planet-warming gas.

Brazil has lost about 339,685 square kilometers (131,153 square miles) of mature rainforest since 2001 — an area roughly the size of Germany — and more than a third of that loss was in Para, according to Global Forest Watch. Para alone accounts for about 14% of all rainforest loss recorded worldwide over the last 24 years.

Gorete, with her small herd, said the tagging hasn’t been much of a hassle. And she sees the program as a good thing. It will let her sell her beef to companies and countries whose consumers want to know where it came from.

“With this identification, it opens doors to the world,” said Gorete, who before cattle ranching cultivated acai and cacao. “It adds value to the animals.”

Cows can move to several farms in their lifetime — born on one pasture, sold to a different farmer, or two or three or more, until they’ve grown to their full weight and are sold to a processor, said Marina Piatto, executive director of the Brazilian agriculture and conservation NGO Imaflora.

Tracking those movements effectively can be a way to discourage deforestation. That’s where the tagging comes in.

Starting next year, all cattle being transported in Para have to be tagged. Each animal actually gets a tag in each ear. One is a written number that is registered with the government in an official database. The other is an electronic chip that links to the same information as the number registered to the cow — like when and where it was born, where it was raised, the owner, the breed and more. By 2027, all cattle in Para, including cattle born on ranches in the state, have to have tags.

Once a tag is removed, it’s broken and can’t be put back, a measure to help avoid fraud.

When the cattle moves, owners are required to report those movements and buyers are required to log the transaction. To be able to sell their animals, ranchers must have tags and a clean history. Locations registered with