Pan Daijing on how power, strength and alienation notify her extensive work as a artist and artist.

This function was initially released in Fact’s A/W 2020 concern, which is readilyavailable to purchase here.

Under various situations, Fact would love to be able to start an essay on Pan Daijing’s work with an encounter. Daijing—born in Guiyang, a city in southwestern China, and based giventhat 2016 in Berlin — makes audiovisual efficiencies that, especially of late, have a stake in liveness that breaks with the current hopes of artists and artists, record labels and galleries that a livestreamed transmission will be enough.

Though I’ve invested a great offer of time with Pan Daijing’s tape-recorded music, which is piercing in its own ideal, I sanctuary’t been in the space for any of the major operas she has staged in the last numerous years (most justrecently, Dead Time Blue at Berlin’s Martin Gropius Bau in January 2020, and late 2019’s Tissues in the Tanks of the Tate Modern in London). The paperwork of these occasions quantities to an insufficient multisensory collage: hours-long choices of video and audio, still photos, Daijing’s composing. To piece together a work as if these disciplinary components — all of which have an adjoined and inextricable location in the artist’s practice — are insomeway unique appears to guide me, the remote audience, in the incorrect official instructions.

But when we speak over FaceTime, Daijing’s upcoming operas are on timeout anyhow. Even previously the coronavirus overthrew the production schedules of practically everybody included in making and distributing art, live or otherwise, she was attempting to take a break in order to figure out what to make next. She thinksabout researchstudy the foundation of her practice, however what makesup researchstudy is for her extensive, encompassing what one may call field work (touring and carryingout live) as well as reading (generally in viewpoint and psychology) and enjoying movies. Even listening to music hasactually been rather on hold, as it appears to trigger too much in her mind—though she’s found satisfaction of late, she states, in listening to old Burial, concrete music, and makeup tutorials.

Solitude, she informs me, is in her view vital to preserving the “pure state of mind” required to do genuine and initial imaginative production: “In Chinese viewpoint, we talk about this figure playing his ancient instrument alone deep in the mountain. The keepsinmind are sparse and easy, nearly mixed into his sonic environments, however you can hear his state of mind in its sound, and that’s how he talks to the mountain, which was his just business. I grew up in a city which is developed 1200 meters high in the mountains, and I see myself like that.” And yet, since of the needs of her exploring and production schedules, such privacy hasactually been challenging to come by. “I’ve been attempting to stay on the peaceful side so that I can clear out the fog and let things expose themselves to me,” she states. “The philosophical being typically comes after the physical and emotional being and I desire to offer more possibilities for that personality to speak up.”

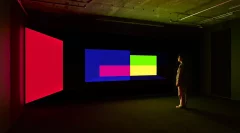

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, to usage something like a musing as a point of entry. Near the end of our discussion, and attempting to get a sense of what’s to come, I ask her what area, without restrictions, may be the perfect place for a upcoming work. Daijing states a action she offered to a manager’s post-opening “What’s next?” question: “It would be actually incredible if I might snatch the audience and bring them on a appropriate journey without them understanding that they’re being taken to a location,” Daijing states. The principle of a “trip”, in the psychedelic sense, has currently been tossed around throughout our discussion in recommendation to the capability of sound: “I would develop an experience that they felt is unique and simply for them, like something they wouldn’t anticipate—and for me as well: I wouldn’t understand who or how numerous individuals are coming. I would desire to work with a really tidy area, like a desert or a cliff by the sea. Very verylittle color, simple things: simply one small individual in this excellent huge huge space. And then we’d do the performance in this area, everybody together in this substantial space.” Everyone together in this big void: there’s a binding concept for what Daijing makes possible.

In order to discover a language with which to call forth this space — a lonesome and serious procedure — Daijing hasactually taken on numerous functions and media, integrating sound, motion and image. One less abstract—and likewise less holistic, and honestly more dull — method of explaining what she does may be finding it at the so-called crossway of speculative music and the art organization, within a growing accomplice of artists whose work, stemming in sound, has spilled out of the containers provided by music places and record labels. It discovers an imperfect, however nevertheless accommodating home in art organizations significantly invested in (live) efficiency; mostimportantly, it likewise discovers financing. In any occasion, Daijing ranges herself from differences, asking us to believe outside of containers altogether. “I puton’t feel comfy labelling myself based on others’ meaning of occupation,” she states. “Whether I’m taking on the function of artist, author, director, entertainer, or designer, I simply view myself as a writer.”

But Daijing’s roots are in sound, and noise is still main: a language, or an option to language, that makes possible some deeply felt interaction and communion from that separated location in the space where Daijing’s work stems. “I’ve constantly worshipped sound, sonic experience,” she states. Conjuring another dreamlike situation, she states an experience on psychedelics where, sitting in a creek, “I felt like all my other senses were subdued, and my ears were massive. And I might hear the water touching the rocks, I might hear the wind takingatrip from far away to touch the leaves. I actually felt like, how big-headed I am, to believe I make music! I wear’t make music, music is there, and my ears are constructed to expose it to me.”

She links this extensive conception of music to the method she knowledgeable noise growing up without music correct as part of her daily life. “To me, sonic experience can be lotsof various things: it can be a vehicle crash, for example,” she discusses. “When I was growing up, I didn’t have music, however I had sonic experiences, so I comprehend the principle of music in a various way.” For one thing, those experiences conjuredup other senses, which, she states, “shows in my work: I personally believe music is method beyond sonic experience. It’s an supreme art type that integrates all these setsoff on the senses.” Memories, landscapes, movies, paintings and motion all call forth this multisensory exchange. An arc kinds out of Daijing’s initially launches as a sound artist, which are developed from searing and unvarnished synthesis, venturing into commercial propulsion however constantly keeping a greyscale asceticism. In the brief window of time inbetween Daijing’s 2015 launching tape for Noisekölln, Sex & Disease, and 2017’s Lack, a full-length album launched by PAN, one can hear the artist broadening her tools of interaction, getting command of brand-new strengths in addition to, and beyond, the roiling electricalpower of pure sound.

The function of the voice on Lack seems in specific a turning point. The music on that record is on the entire extremely managed, establishing a sense of story that was not almost so palpable on Daijing’s earlier releases. It is itself a type of opera, and appears to nod to a less included variation of itself: within a structure, one may ricochet inbetween claustrophobia and an unstable sense of vastness. The record impacts in a spatial, physical kind of method that, one envisions, would just intensify if one shared a space with its components in genuine time. And within this scene, Daijing’s usage of vocals is less an interjection of a human existence than an emulsifying force, a tip that the totality of what we’re hearing is mined from human experience.

Furthermore, the operatic voice within her work—hers, or that of any of the vocalists she directs—complicates the idea of carriedout vocals acting as the source of intimacy within a structure. It’s not constantly natural, nor is it always narrative; or often it’s so natural—guttural, instinctual, a groan or a piercing note more instant than spoken language—that it agitates. The voice, Daijing states, is particular, “the most susceptible instrument a individual has”, one that always changes with time and experience, and one that can be shaped and experienced—though, at least in the case of the entertainers she works with, not always managed. Still, vulnerability and control are cooperative forces within her practice, both officially and in Daijing’s sense of herself as a entertainer. She explains how early in her profession, her openness was fulfilled with being taken benefit of, “even by the audience often”. Rather than disavowing such openness entirely, knowing to self-protect appears to haveactually made possible the vulnerability that she calls “a needed action in my work”: “I’m braver than before. I have the guts to do things I wouldn’t haveactually done.”

Vulnerability is likewise about accomplishing a specific level of exchan