Rewilding and repair of land typically rely on the reintroduction of types. But what takesplace when what you desire to reintroduce no longer exists? What if the animal in concern is not just inyourarea extinct, however gone for excellent?

Yes, this may noise like the plot of Jurassic Park. But in genuine life this is really occurring in the case of the Aurochs (Bos primigenius). This wild forefather of all contemporary livestock has not been seen consideringthat the last specific passedaway in 1627, in today’s Poland.

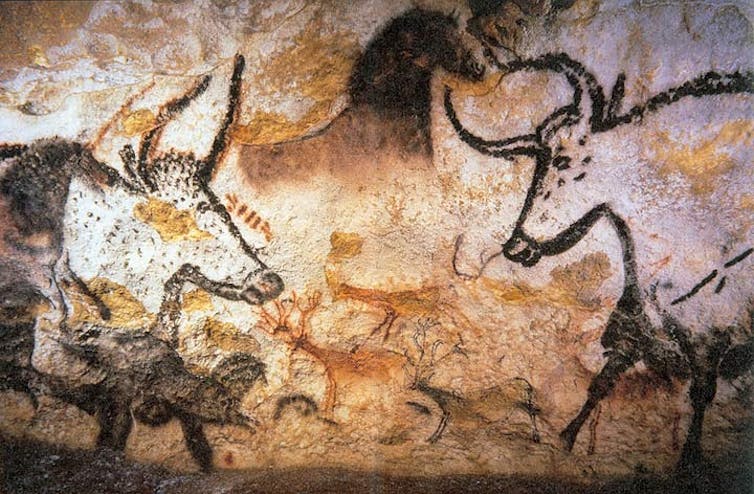

Aurochs haveactually been deep within the human mind for as long as there haveactually been humanbeings, as testified by their prominence in cavern art. However, the introduction of farming and domestication put the stunning animal on a course to termination.

So why bring the Aurochs back today and how? And what is the mostlikely result?

What is left of Aurochs, besides their representation in cavern paintings, are some fossil stays and some descriptions in the historic record. “Their strength and speed are remarkable,” composed the Roman emperor, Julius Caesar, in Commentarii de bello Gallico.

Despite the previous big variety of environment of this animal (from the Fertile Crescent to the Iberian Peninsula, from Scandinavia to the Indian subcontinent), the historic record is rather slim on specific descriptions. And in all probability its size, behaviour, and basic character will have differed throughout various environments. Despite this mostlikely variation, the Auroch has madeitthrough into modernity as the prehistoric, effective and massive, ox.

A super-bull

The concept around today is that the Aurochs’ qualities have madeitthrough, genetically spread throughout its descendants. By breeding these together and picking offspring that program progressively more Aurochs-like qualities, the theory is that we can ultimately re-create something extremely comparable to the lost animal. This theory is understood as back-breeding: actually reproducing inreverse.

The veryfirst effort to restore the Aurochs was made in the 1930s in Germany by 2 zoo directors, the siblings Lutz and Heinz Heck, with an indisputable Nazi celebration association.

Their production, now understood as the Heck livestock, took just 12 years to achieve and blended types of domestic livestock with battling bulls from Spain. The bros focused more on size and aggressiveness than on being faithful to the physiological description of the Aurochs. This is partially why noone today thinksabout Heck livestock to be real entertainments of an extinct types, something showed in the name these animals bring.

The Heck livestock made it through World War II and have giventhat inhabited pastures and zoos throughout Europe. Though definitely not Aurochs, lotsof discover that they do the Aurochs’ task simply fine. This is why the well-known Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve in the Netherlands utilizes them as one of their main grazers.

Recreating wilderness

For most of the 20th century it was presumed that the landscape in Europe before human settlement was primarily forest. Frans Vera, a Dutch biologist, altered this acquired knowledge and proposed that the primeval European landscape was a mosaic consisting of forest as well as meadows and other kinds of environment. One of the primary factors for this, he argued, is that huge animals (the Aurochs amongst them) would haveactually crafted this landscape through their grazing behaviour, something now understood as “natural grazing”.

The Oostvaardersplassen, established by Vera, is his method of proving that he is . The herds of Heck livestock were presented to engineer the landscape, to see what takesplace to the land in the existence of numerous grazers.

The theory of natural grazing has broughtin lotsof that are excited to present grazing animals to brand-new land, in the hope that they will endupbeing the engineers of a future European wilderness. This push for wild grazing animals is one of the main elements behind the drive to recreate the Aurochs.

As the world is urbanising, rural land is being deserted. In Europe, it is forecasted that farmland desertion will continue apace through the middle of the century.

This altering land-use pattern throughout