Climate work is not about diluted commitments coldly discussed in a boardroom. It is about knowing and feeling all that is at stake – like parenthood.

Kealoha Fox, Maya Soetoro-Ng and Zelda Keller

| Opinion contributors

As mothers, we have often felt engulfed by the gnawing worry of climate change, the jagged feeling akin to that moment when you, as a mother, drop off your child in the care of someone who hasn’t yet earned your trust. You see your child’s bright, observant gaze. Their nerves express concern to you with quiet messages designed to tug at your unique receptivity – a tight squeeze, a shifted foot, a tear in the corner of the eye. And you ask yourself: What if they are imperiled and unprotected when I am not present?

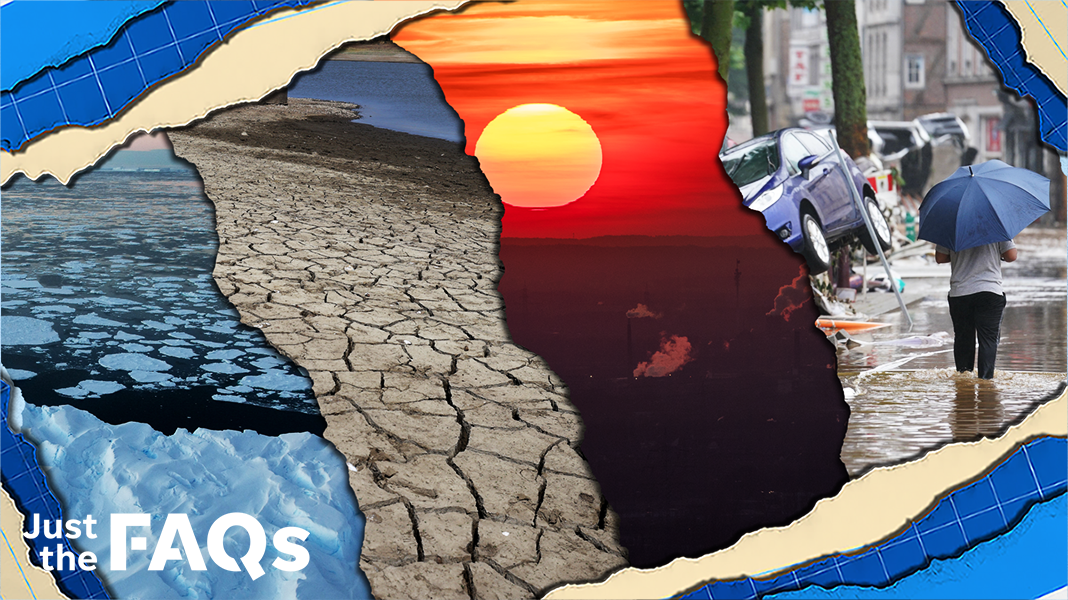

When we read the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports in February and April, which United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres described as an “atlas of human suffering and a damning indictment of failed climate leadership,” the anxiousness about our children’s well-being was rekindled in all of us.

The three of us form the backbone of the Institute for Climate and Peace, a nonprofit organization based out of Hawaii focusing on the intersections between climate change and peace. We know how precarious the situation is. And we know that many of our leaders – well-intentioned as they may be – are ignoring the truest solutions to bring about peace and climate resilience. Central to our climate justice work is helping to frame the conversation about what peace is.

‘Positive’ peace can help heal planet

Historically, peace has been too often confused with the topic of security and defined simply as an absence of war and violent conflict, otherwise known as “negative peace.” However, there is another type of peace: “positive peace,” which means the presence of active systems and processes that allow human potential to flourish.

Many systems that led to positive peace were integral to ancestral communities but dissipated during the industrial revolution. Indeed, technology has provided many boons to civilization, but it has led directly to our climate crisis, and now technology alone cannot get us out of this emergency.

WHO director: With world in crisis, we must push for peace to save millions of lives

Positive peaceful climate solutions present the greatest opportunity to build social cohesion, create lasting commitments that survive beyond partisanship, and are sustained beyond each of us. Our work, which complements broad efforts to reduce emissions, focuses on locally rooted, more tailored measures. This includes things like the preservation or restoration of cultural assets on our coastlines, just and dignified migration, democracy building and gender inclusive leadership.

Climate change presents differently in each community, as do the threats to peace and stability, so we believe a process, rather than a predetermined prescription, is the best answer, one that develops custom-designed remedies as well as trust and unity.

Not a reason to celebrate: U.N. climate change report says we’re on the path to an ‘unlivable’ planet. WE DID IT!

The IPCC report highlights the need to reduce climate risks for the most marginalized through adaptation. However, its framing of front-line populations as inherently vulnerable and in need of top-down solutions and saving fails to make space for the positive peaceful solutions that are most successful and achievable. It also overlooks the inherent wisdom and lived experience of front-line communities and their ancestors.

This is not to say we shouldn’t set ambitious goals grounded in science; it just means we cannot afford to neglect positive peaceful climate solutions grounded in social sciences if we are to truly build the shared future we imagine for our children.

To cite just one statistic: Natural disasters kill 13 times as many people in regions with low levels of positive peace (characterized by well-functioning governments, strong community relations and equitably distributed resources, among other indicators) than in regions with higher levels of positive peace.

Linking climate and social science

That is why our institute is dedicated to a new narrative: Climate science and social science are integrated, collaborative fields helping to advance community-based climate solutions for thriving, cohesive communities.

Through our research, training, educational workshops, policy guidance, community partnership development and mentorship of young women leaders, our intention is to be in the right relationship with each other and the Earth. We are certainly not the only organization engaged in peace work, but we are one of the few that recognize it as being inextricably linked to climate work. Our Pasifika communities have long promoted imaginative, place-based and interdisciplinary climate and policy initiatives.

Climate change: As Hawaii declares climate crisis, schools hope Indigenous knowledge will save the islands

On the island of Oahu, we find community-led Indigenous systems regeneration and educational initiatives about the value of these sacred ecosystems through the wisdom of ancient Hawaiian protocols. On Lanai, a high school English teacher has worked to build intergenerational connections through a multiyear, student-led community research project about food sovereignty. Her work has helped to connect a small community’s youth with its elders and revived locally grown, culturally significant produce like breadfruit.

We also see traditional technology at work through the restoration of sustainable mechanisms for catching fish, or reviving turtle populations using tide flow and deep-rooted aquarian knowledge.

Columnist Connie Schultz: I lost my sense of smell but I still inhale the world, and I like this version of me better

The communities and lands where these projects are based are now stronger, healthier, more connected and better prepared to face climate impacts with resilience. These projects are all examples of climate work, even though they are not explicitly designated as such, nor are they given the resources, attention and integration into larger-scale climate policy and funding initiatives they deserve.

Despite the demonstrated successes of locally based efforts like these, governments and philanthropies invest most climate finance in top-down and technology-centric approaches. An International Institute of Environment and Development assessment of climate finance between 2003 and 2016 estimated that less than 10% went to locally led climate change projects.

One of the bigges