How does an organization with 100 years of history stay relevant, adaptable, and forward-looking? Bob Sternfels, who runs McKinsey & Company as the Global Managing Partner, has led the company through a wave of recent challenges while trying to plan the road ahead for the consulting industry leader. He explains the balance he’s aiming to strike between AI agents and human employees, how he’s handled moments of scrutiny, and the ways in which he’s been working to build trust both internally and externally.

ADI IGNATIUS: I’m Adi Ignatius.

ALISON BEARD: I’m Alison Beard and this is the HBR IdeaCast.

ADI IGNATIUS: All right, Alison, this question’s going to seem random, but I promise you it’s not, what was your major in college?

ALISON BEARD: I was a double major in journalism and politics at Washington and Lee University.

ADI IGNATIUS: Okay. I was history at Haverford, another liberal arts college. If you’re like me, you probably figured that your majors equipped you well for something like journalism, but maybe not so well for something like management consulting, which is tended to recruit people who studied economics or engineering or business.

ALISON BEARD: Yeah, I always thought of consulting and finance as the place where all the most ambitious, highest achievers, most capitalistic students wanted to go and those firms definitely focused on the Ivy League and the big universities.

ADI IGNATIUS: The world is changing. We know that AI is remaking everything including the world of management and my guest today, McKinsey’s global managing partner, has a lot to say about how it is rethinking its business in this era.

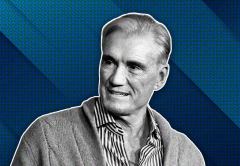

So McKinsey already views its first AI agents as very much part of its workforce and is rapidly expanding that part of its team, but while AI is really good at linear problem solving, it’s not so good at out-of-the-box thinking, which means McKinsey is rethinking its talent needs. I’m not going to spoil it, but your journalism politics double major might line up well with what the consulting giant is increasingly looking for. So here’s my interview with Bob Sternfels, global managing partner at McKinsey, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year.

So I want to start, McKinsey is turning, maybe has turned 100. HBR, by the way, we’re 103, so welcome to the Century Club. How would you summarize the company’s 100-year legacy? To what extent has McKinsey created the ideas that have shaped the business world or to what extent is it about identifying and suggesting best practices that come from elsewhere?

BOB STERNFELS: I guess I would start with the nature of how we do our work. And the idea is, look, we co-create with our clients and when we’re at our best, it is figuring out how do we help clients get to places they can’t get to themselves. The whole notion in some ways of credit of, “Did you create something novel or did you have best practice?” maybe the way we frame is we’re co-creating with clients to help them come up with things that they may not have come up with themselves or we might not have come up with themselves.

And we clearly invest a boatload in proprietary IP. We invest over a billion dollars a year in innovation, new thought, new ideas. Our McKinsey Global Institute, for example, which is a bit of our independent research tank, but we’ve now created McKinsey Health Institute, I think if you do look at their history, a lot of that is novel thinking, the most recent looking at a global balance sheet and saying, “How’s the world when you look at assets and liabilities?” That’s not a best practice, that’s new thought. But equally, part of the reason we stay global as an operating model is, then at the more micro levels, the clients that we serve don’t want to understand what the leading edge innovation is in their particular country.

They want to understand innovation around the world and perhaps even cross sector. And that is part of our model. So I’d probably say, if I had to guess, it’s probably half-half on this around where are there truly novel co-creation and where is this idea of figuring out, “How do you bring innovation around the world to clients who may not have access to that innovation based on the reality that they’re in?”

ADI IGNATIUS: So one area of innovation obviously is AI and I’m sure you’re advising companies all the time on how to adapt to an AI-driven world. I want to talk about that, but I’m interested in the internal discussions that are happening at McKinsey about this. To what extent is AI shifting the economics of your industry, headcount, pricing, productivity? Are margins improving? Are they under stress? What are the internal conversations about AI for your business?

BOB STERNFELS: AI, we haven’t talked about that at all. No, I’m just kidding.

ADI IGNATIUS: You should. It’s really cool.

BOB STERNFELS: It’s hard to have a conversation in any context right now that doesn’t link back to some form of AI. I think this question around AI and how it impacts McKinsey, there’s two sides of that coin. There’s a client-facing side and then there’s, “What are the implications on McKinsey?”

There’s a unique moment to help all of our clients reimagine themselves leveraging this technology. And to be able to do that, we have to rewire ourselves to be able to deliver that. I may audio just start with a bit of what I’m actually hearing from clients around the world, across all industries and across all geographies and I really hear in the truth room maybe two things. On the one hand, an enormous belief in the potential for this wave of technological change and that’s everything from enormous productivity gains in areas like customer care or back-office processes, but also to growth things. If you think about radically shortening the time of drug discovery and what that actually means for longevity and life and that’s top line growth.

So folks are excited and they’re believers, but at the same time, from the conversations that I have with CEOs, they’ll often say, “Hey, Bob, so do I listen to my CFO or my CIO right now? My CFO is in my ear that we’re spending a lot of money on technology, but we’re not yet seeing enterprise-level value from this. And so do we really need to be at the cutting edge or why can’t we be a fast follower, let other folks figure out where this is and then we’ll adopt quickly because it’s a lot more efficient to be a follower than a leader? CIO is saying, ‘Are you crazy? This is one of those moments. And if we’re not in the lead, we’re going to get disrupted.’”

We’ve spent a lot of time looking at at least what we think the answer is here and I know we spent a lot of time talking about technology, but what we’re finding is half if not more of the secret sauce is organizational change as opposed to technology implementation. This is for large enterprise. And it’s things like, “Well, what does your work look like after you’re implementing these? Could you have, for example, a much flatter organization that cuts out a lot of middle layers and makes your organization faster?”

When you think about really complicated workflows, think about a mortgage process, you got all these steps, origination, credit scoring, collection, after service, et cetera. Those are all departments in a bank. Well, why do you have four or five departments in a process if you can really enable this through AI? Can’t you break those walls down? And so we’re spending a lot of time thinking through not only what’s the strategy and how do you implement, but how do you change the organization? How do you rewire the organization to realize the value?

And if you can get that right, all of a sudden, the CFO and the CIO are actually on the same page, but we’re finding that’s harder and it’s taking longer than people thought. And so I do think we’re going to be in this period where really enterprise fundamentally changing themselves, yes, enormous potential, it’s going to take a little while to get there.

So then you say, “Okay, what does that mean for McKinsey?” We’re applying this to ourselves. I often get asked, “How big is McKinsey? How many people do you employ?” I now update this almost every month, but my latest answer to you would be 60,000, but it’s 40,000 humans and 20,000 agents.

Little over a year and a half ago, that was 3,000 agents and I originally thought it was going to take us to 2030 to get to one agent per human. I think we’re going to be there in 18 months and we’ll have every employee enabled by at least one or more agents. That’s one piece of what are the assets and technologies that we’re building in ourselves.

The other big piece is how does it change our model. We’re coming around to the conviction that we’re migrating pretty quickly away from, let’s call it pure advisory work, which was a lot of the origins of our firm and a fee-for-service model, et cetera. And what’s it moving to? It’s moving to much more of an outcomes-based model where we say, “Look, let’s identify a joint business case together and we will underwrite the outcomes of that business case.” And it aligns our interests with our clients a lot more and I think will be the way of the future.

ADI IGNATIUS: Yeah. Now, AI is going to get better, right? We’re still in the-

BOB STERNFELS: It is, yeah.

ADI IGNATIUS: … early phases of generative AI. If technology can continue to commoditize even the kinds of analysis and insight that a McKinsey has long provided, what will clients actually be paying for when they could probably do a lot of that themselves?

BOB STERNFELS: The kind of problems that we have tackled with our clients over a hundred years has not been static. It has changed radically. I’m now considered a dinosaur in our firm because I’m a little over 30 years with us, but the stuff that I did when I joined as an associate 32 years ago, we wouldn’t consider even doing right now. Why? Because clients do that stuff themselves and we are solving much more complicated interconnected questions with our clients.

And I think what this is going to then mean is this is just going to be that next evolution of there’ll be a whole bunch of things that a couple years ago we did for our clients that our clients will do for themselves and the imperative will then be to move to the even more complicated questions. And to your point, what are clients going to pay us for? They’re going to pay us to find ways to double their market cap. And until we get to CEOs who say, “I don’t want to double my market cap,” I think there’ll always be a more complicated set of questions and opportunities out there.

ADI IGNATIUS: What is the evolving skills profile then of a management consultant? Do you even know yet? What are you looking for in new hires and that must be evolving pretty quickly?

BOB STERNFELS: This is a really fascinating question. It’s a passion of mine. I might frame it in, “What are some things we’re confident about now and then what are some things we’re exploring?” When I came into this role, and it was a little over four years ago, I asked our talent attraction team, “How are we doing on attracting talent?” and I got a, “We’re doing great, Bob. We’re doing great.” I said, “Well, why?” They said, “Well, we get over a million applications a year and we hire anywhere between eight and 10,000 people. And even the million aren’t a normal distribution. They’re some of the brightest minds in the world that are applying. So effectively, what’s the problem? Why are you asking me? Let me go back and do my job.”

And I kept asking the question, “But, well, how many profiles are we really looking for? What are we systematically screening out?” and it turned out that really, when you boiled it down worldwide, there’s only 500 pathways that would lead you to McKinsey. And that wasn’t tying with what our own organizational research was saying, that the half-life on skills was getting shorter, that people were too focused on paper ceiling because you have the right credentials. And so we actually applied analytics on ourselves and took the last 20 years of data and said, “What are the skills and characteristics that are most likely to make partner in McKinsey?” because it’s not perfect, but it’s a marker of success. Only one in six hires make partner.

And it turned out we had some bias in our system. We had 50 different implications, but I’ll give you the biggest three. One was that we were too focused on, “Did you have perfect marks?” versus, “Did you have a setback and recover?” And the applicant who had a setback and recovered was more resilient and more likely to be a higher probability of making partner in McKinsey and we weren’t screening for that. So we’ve