This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: In this Democracy Now! special, we’re joined by one of the world’s most acclaimed writers, Arundhati Roy, author of many books, including the novels The God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Roy has been a frequent guest on Democracy Now! for over two decades, talking about her novels, as well as her nonfiction work and her activism. She’s been a vocal critic of U.S. foreign policy, from the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq to the U.S. arming of Israel.

In India, she has been repeatedly targeted by authorities for criticizing Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his far-right ruling BJP party. In August, authorities in Indian-occupied Kashmir banned a list of books, including her collection of essays titled Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction.

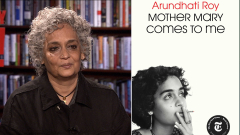

Earlier this year, Arundhati Roy published her new memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me. The critically acclaimed book focuses on her mother, the celebrated educator Mary Roy, and how Arundhati was shaped by her, both as a source of terror and of inspiration. The Times writes, quote, “In this unsparing yet darkly funny memoir, the prizewinning novelist captures the fierce, asthmatic, impossible, inspirational woman who shaped her as a writer and an activist — and left her emotionally bruised for a lifetime,” unquote.

In September, Democracy Now!‘s Nermeen Shaikh and I spoke to Arundhati Roy. We began the interview by asking her about the title of her book, which is based on the lyrics of The Beatles’ song “Let It Be.”

ARUNDHATI ROY: The title, I think it chose me. You know, The Beatles play a big part in the book somehow, even though it was a little after my — I mean, I was a little late for them, but I loved that music, and it gave me the sort of steel in my spine and the smile on my face to leave home, which I did when I was 18, for a whole host of reasons. But I did listen to “She’s Leaving Home” on a loop, you know, weeks before I left. And, of course, it was interesting, because the book was launched in Cochin in St. Teresa’s Girls’ College, and the hall, by chance, was called Mother Mary Hall. Then my brother sang, “Let It Be.” And I said, “Well, there are three Mother Marys here: One is the Virgin Mary, one is Paul McCartney’s mother, and the third is ours. And they are all very different.”

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, your first book, God of Small Things, is also dedicated to your mother. You wrote, “She loved me enough to let me go,” which your brother joked was the only bit of real fiction in the book.

ARUNDHATI ROY: Yes. Well, when I wrote The God of Small Things, you know, I had, of course, left home and lived as a adult for many years. I mean, I put myself through architecture school, working and all that. And we never — I mean, there was years of estrangement. She never asked why I left or what happened or anything. She didn’t need to, because we both knew. And I was aware that the — you know, she was still the principal of a school she founded in this small town, and for her to have a daughter leaving would have been something —

AMY GOODMAN: At the age of 16.

ARUNDHATI ROY: Yes, and it was a very complicated thing, The God of Small Things, too, you know, coming out in that town. So, I said we settled on a lie, a good one, which I crafted, and I said she loved me enough to let me go, which my brother jokes was the only piece of real fiction in the book. But, yeah, it was just — you know, all my life, I had to sort of manage this relationship with a woman who was amazing and also very, very dark, you know? And so, as I said, in order for her to shine her light on her students and generations of them to challenge a law, which eventually she won, and Christian women won equal inheritance rights.

AMY GOODMAN: Just talk about that for a minute, and then we’ll go into the internal, deeper, darker place. But what she was to India and to women?

ARUNDHATI ROY: So, she — I mean, she came from a very small community of people who live in Kerala called the Syrian Christians, very — let’s say, very — I won’t say elite, but, you know, a very protected, yeah, somewhat elite, you know, land-owning, for the most part, people, very conservative, very parochial. And then she married, outside of the community, my father, and then got divorced and came back. And she had no money and nowhere to go, and she was living in a little cottage outside of Kerala, which belonged to her rather cruel father, who had died by then. And her mother and brother — we were little. I was 3, and my brother was 4. And her mother and brother came and tried to evict us by saying that, according to the Travancore Christian Succession Act, women could inherit a fourth of what a son could, or 5,000 rupees, which is, you know, at that time, a little bit of money, but whichever is less — in effect, couldn’t inherit.

So, she — you know, she nurtured this mortification, and she waited for — she started — you know, once she came out of this poverty, she started a little school, and it became a huge success. It is a huge success. And when she had the means, she challenged the law and said it was unconstitutional. And eventually, it was struck down by the Supreme Court, and women, Christian women, were given equal inheritance rights. So it was revolutionary, but so was her school — and so is her school, a really amazing place, you know? So, I was always able to see this public figure, who was extraordinary, and, you know, there was some other story going on in private.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: I mean, there’s several incidents in the book. We want — I’ll go back to the things that you said earlier about your decision to leave home when you did, but your mother’s extremely strong personality, her courage. She was a radical feminist, bold and uncompromising, in perhaps all aspects of her life. But you — so, first, if you could give us a couple of examples of that from the book? But then, you write that the way that your mother treated your brother has, quote, “queered and complicated” — this is you writing — “queered and complicated my view of feminism forever, filled it with caveats.” So, if you could explain that for us, a couple of examples, and then what happened?

ARUNDHATI ROY: So, I mean, you know, when people label her like a radical feminist or something, those labels don’t sit well with her or me, because she was so eccentric and so nonrighteous about what she did, and she was such a wild character. So, I wouldn’t, you know, use those words to describe her. But, yes, she was an iconic person in feminist circles, because — especially because of the case that she won, less so because of the school, because fewer people know about the school. But to me, it’s as revolutionary. And when she — we lived in this little town where there was so much conservativeness and all kinds of passive and active violence against women. And she would just go into courtrooms, to hospitals, to places where she had heard, you know, women had been beaten up or raped or whatever, and she would try and tell them, “Look, there’s an option. You don’t have to be like this.” You know, so, it was — it was a wonder to watch that.

But at the same time, she was my — I mean, she had left my father because he was addicted to alcohol. I didn’t know my father ever, and — until I was about 25. And she would — she’d be very — she was hard on both of us, but especially on my brother. And so, there’s a part in the book where my brother was a little older than me, so he suffered the pain of losing his father or of having this crazy, violent, single parent, you know? And from being a really wonderful, excellent student, he just began to drop in his grades. And we were sent away to another school, because her school did not have classes up to, you know, class six and seven and so on. So we were sent away.

And there’s an incident where one night our report cards came, and we were both awake, and she came and took him at night to her room. And I followed and looked through the keyhole, and I saw — I saw her just beating him ’til the thing broke, and sort of shout — shouting in a whisper, because the school was also — our home was also the hostel for little children, and saying, “No son of mine can come with a report that says average student.” And then, in the morning, he came back to bed, and we both knew — we were awake. But in the morning, she came and hugged me and said, “You have a brilliant report.” And I just felt like I just hated myself. And I felt like — even now, I feel, you know, that if ever I’m sort of celebrated, there’s someone quiet being beaten in the other room.

And that, from being a very personal thing, has also become a very political thing. And I know that as my book comes out, what is going on in Gaza, you know, children are being starved. Hospitals are being bombed. A whole genocide is taking place in public light. And we have to continue to do our work, always cognizant of the fact that it’s not just one thing that’s happening to you. You know, many things are happening, and the quiet person is being beaten. Yes.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: I mean, one could say that, in fact, you dedicated your life, as a result, to being with those who are being beaten, or at least standing in solidarity with them.

ARUNDHATI ROY: Yeah, I mean, “dedicated” sounds a little pious. But for me, I think what happens is that once you’ve — once you’ve been unsafe in that safest place — I suppose the safest place is the mother. And once that is unsafe, safety is very hard to find again, and you’re constantly — you’re constantly aware of the unsafe, you know, constantly aware of that other thing that’s happening, and unable to sort of settle into safety in some way.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, the way you describe how she beat your brother and then congratulated you, it is not as if you were the favored child. I mean, after your mom passed away a few years ago, and you were so wrecked by it, your brother said to you, “She treated nobody as badly as she treated you.” Talk about your relationship with your mother.

ARUNDHATI ROY: Well, both of us believe that of each other. You know, I think that she treated him worse, and he thinks she treated me worse. But the relationship was — you know what? I think what happened was, to me, I could see it almost like a chemical experiment, you know, like a chemical reaction, because she had left her husband, and she was living in this conservative community. She was being humiliated. She was being evicted. She was being, you know, whispered about. And all the anger that accumulated, the only safe harbor she had to unload it on was me and my brother, you know? And it’s — so, it’s such a patriarchal community, so they used to call us, in Malayalam, ”adrasillatha pilleru,” meaning the children with no address, because we didn’t have a home as such, you know, a parental place. And with me, I mean, she — I think she — you know, I came along at a time when her relationship with her husband was already over, so she didn’t want another child. And, I mean, now as an adult, I can understand it. But —

AMY GOODMAN: And she made it clear to you.

ARUNDHATI ROY: Yeah. She kept saying, “I wish I had dumped you in an orphanage,” and all this.

AMY GOODMAN: Or that she had had an abortion.

ARUNDHATI ROY: Yes. And then she — and at the same time, she also reinforced me by — you know, because it was made clear to me that I’m on the edge of this community, not at the bottom, but on the edge, and its reassurances were not for me, the arranged weddings and the protections and the whatever. So, she knew that I had to — I had to go, like I could not be there, you know? And she — in some ways, she prepared me, but sometimes it was harsh. Like, she just kept telling me, “I’m going to die,” because she was a very, very severe asthmatic. And so, there was this constant thing of “Any moment, I’m going to die.” And I was like her spare lung. I was like breathing for her, you know, and saying, “I’ll breathe for you.” And then, as I grew up, that sort of dependency obviously began to change. And for her, it was a hostile thing, you know?

And so, of course, like, there’s a part in my book where I say she taught me how to write, then she raged against the author I became, and she taught me to be free, and then she raged against my freedom. But she did — she did put that steel in my spine, you know? And she did teach me something in harsh ways, which did help me survive, you know, on my own in a city. You know, from Kerala to Delhi, it’s like three days and two nights by train, and you don’t speak Hindi, and you don’t know what’s going on. But at the same time, there was that sense of I’m just looking for a better life. I’m not looking to suffer here. You know, I’m looking for some joy. I’m looking for some happiness. I’m looking for something great to happen, not as an ambitious, but, you know, surely things are going to be better. You know, that’s why I left. And I say that in the book, not because I didn’t love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her.

To me, the book was a writing challenge, you know? Like, can I — can I share with people a person that you simply cannot make up your mind about, you know? Because there are so many wonderful things and then terrible things and then wonderful things, and it just keeps turning over and over. I keep saying she’s like an airport with no runways, like you can never land your plane. And also, there are so many people who are people of — you know, who have a calling, whether they are musicians or whether they are politicians or whether they are poets or, you know, so many people who — whose primary concern may not have been their own children, you know? But in my case, my mother’s calling was other people’s children, you know, which was what made it a bit complicated for us, why we had to call her Mrs. Roy, because, you know, we were just students in her school and so on. But yeah, it was — it was continuously that process of, you know, being gifted something, and then being shredded, and then — you know, but learning to hold on to those gifts, you know, and not let them smash along with the shredding.

AMY GOODMAN: You not only called her Mrs. Roy in public, because she didn’t want you to seem favored, and you felt that maybe she was harsher on you and your brother so that you wouldn’t seem favored, but you also called her Mrs. Roy privately.

ARUNDHATI ROY: But we didn’t have any private, you see, because what happened was that she started a school initially in the rented halls of Kottayam Rotary Club. We had to go with brooms every day and sweep up all the men’s cigarette stubs and wash all their glasses and put them away, put