(Image credit: Alan Dyer/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com’s Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Jonti Horner is an astronomer and astrobiologist based at the University of Southern Queensland, in Toowoomba, Queensland.

Hot on the heels of the disappointing Green Comet, astronomers have just discovered a new comet with the potential to be next year’s big story – C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS).

Although it is still more than 18 months from its closest approach to Earth and the sun, comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS already has social media buzzing, with optimistic articles being written about how it could be a spectacular sight.

What’s the full story on this new icy wanderer?

Related: Bright new comet discovered zooming toward the sun could outshine the stars next year

Introducing comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS)

Every year, a few dozen new comets are discovered – dirty snowballs moving on highly elongated paths around the sun. The vast majority are far too faint to see with the unaided eye. Perhaps one comet per year will approach the edge of naked-eye visibility.

Occasionally, however, a much brighter comet will come along. Because comets are things of ephemeral and transient beauty, the discovery of a comet with potential always leads to excitement.

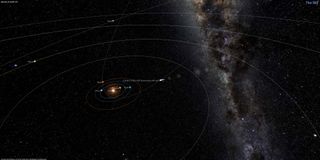

Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) certainly fits the bill. Discovered independently by astronomers at Purple Mountain Observatory in China and the Asteroid Terrestrical-impact Last Alert System, ATLAS, the comet is currently between the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn, a billion kilometers from Earth. It is falling inwards, moving on an orbit that will bring it to within 59 million kilometers of the sun in September 2024.

The fact the comet was found while it’s so far away is part of the reason for astronomers’ excitement. Although currently some 60,000 times too faint to see with the naked eye, the comet is bright for something so far from the sun. And observations suggest it’s following an orbit that could allow it to become truly spectacular.

A recipe for comet greatness

It’s all down to a combination of the comet’s path through the solar system, and the potential size of its nucleus – the solid center.

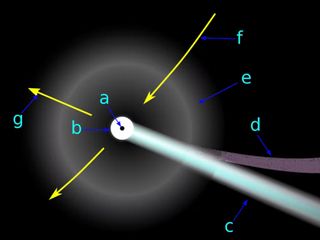

As comets swing closer to the sun, they heat up, and their surface ices sublime (turn from a solid to a gas). Erupting from the comet’s surface, this gas carries along dust, shrouding the nucleus in what’s called a coma – a giant cloud of gas and dust. The coma is then pushed away from the sun by solar wind, resulting in a tail (or tails) pointing directly away from the sun.

The closer a comet gets to the sun, the hotter its surface becomes, and the more active it will get. Historically, the vast majority of the brightest, most spectacular comets have followed orbits that brought them closer to the sun than Earth’s orbit. The closer, the better, and Tsuchinshan-ATLAS certainly ticks that box.

In fact, this new comet seems to tick all the boxes. It appears to have a sizeable nucleus, making it brighter (bright enough to be discovered so far from the Sun). It is destined to have a very close encounter with our star. And, the kicker, it will then pass almost directly between Earth and the sun, approaching within 70 million kilometres of us just two weeks after perihelion (the closest approach to the Sun). The closer a comet comes to Earth, the brighter it will appear to us.

Put that together, and you have a recipe for a comet that could shine as brightly as the brightest stars. Some forecasts are even more bullish, suggesting it could be up to a hundred times brighter still!

The curse of prediction

Predicting how newly discovered comets will behave is a dangerous game. Some may be spectacular, while others fizzle.

Take, for example, comet Kohoutek, in 1973. Like Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, Kohoutek was discovered unusually far from the Sun, moving on an orbit that swung close to our star. Cue the hype. Astronomers promised the public “the comet of the century,” predicting Kohoutek could become bright enough to see in broad daylight.

But comets are like cats. Kohoutek brightened as it swung in towards the sun, but more slowly than expected. Rather than being visible in broad daylight, it was only as bright as the brightest stars, and faded quickly after perihelion. It was still a good show, but far from the comet of the century. Because of the hype, many dubbed Kohoutek a spectacular disappointment.

It turns out Kohoutek was passing through the inner Solar system for the very first time. It had never come so close to the sun, so its surface was rich in highly volatile ice which began to sublime when the comet was still far away. At that great distance, the comet was much brighter than other, more experienced comets – and that brightness suggested the comet would be truly spectacular.

As it came closer to the sun, those volatiles were exhausted, and the comet’s final activity was less than initially predicted, making it fainter.

There is a very real chance Tsuchinshan-ATLAS might, like comet Kohoutek, be approaching the inner solar syst