Jimo Borjigin never intended to study death. Back in the mid-2010s, the consciousness researcher at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor was instead interested in circadian rhythms, the internal cycles that regulate our physical, mental, and behavioral states throughout each day. The circadian clock is a bit of a black box, Borjigin says, so to study it she and her team developed an automated system to continuously monitor neurotransmitters that regulate circadian rhythms in rats.

Over the course of her research, the scientists tracked the animals for weeks at a time, and Borjigin began to notice something unusual. A few of the animals died while under observation, and when they did, the researchers’ sensors recorded a massive and unexpected spike in serotonin for up to 30 seconds after their hearts stopped beating. In humans, serotonin dysregulation has been linked to intense hallucinations, but Borjigin didn’t know what to make of such a finding in the context of rats. Or in death. Like any good scientist, she looked to the literature.

“I was sure we must know everything there is about the death process already, but when I went looking for evidence of this serotonin spike, I found nothing,” she says. “Looking into the research on death more broadly, I was shocked at how little we truly understand about this thing that happens to every one of us.”

“Cadavers are often in a state of reversibility for hours, if not days, postmortem.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience.

Log in

or

Join now

.

The experience prompted a shift in Borjigin’s research focus, and today she studies consciousness in relation to death and near-death experiences. In 2023, she and her colleagues published a contentious finding: that humans, like her rats, also experience a dramatic shift in brain activity when we die. The team monitored four comatose patients as they were taken off life support, and in two cases, detected a spike in gamma waves—the fastest type of brain wave, most active during periods of intense focus or problem solving—in a part of the brain correlated with dreaming, visual hallucinations, and altered states of consciousness. “To me, this suggests a covert consciousness that is not usually observed by bystanders who might otherwise look at a person and think they are unresponsive,” she says. “If that’s true, it definitely makes me think we need to revisit our definition of death.”

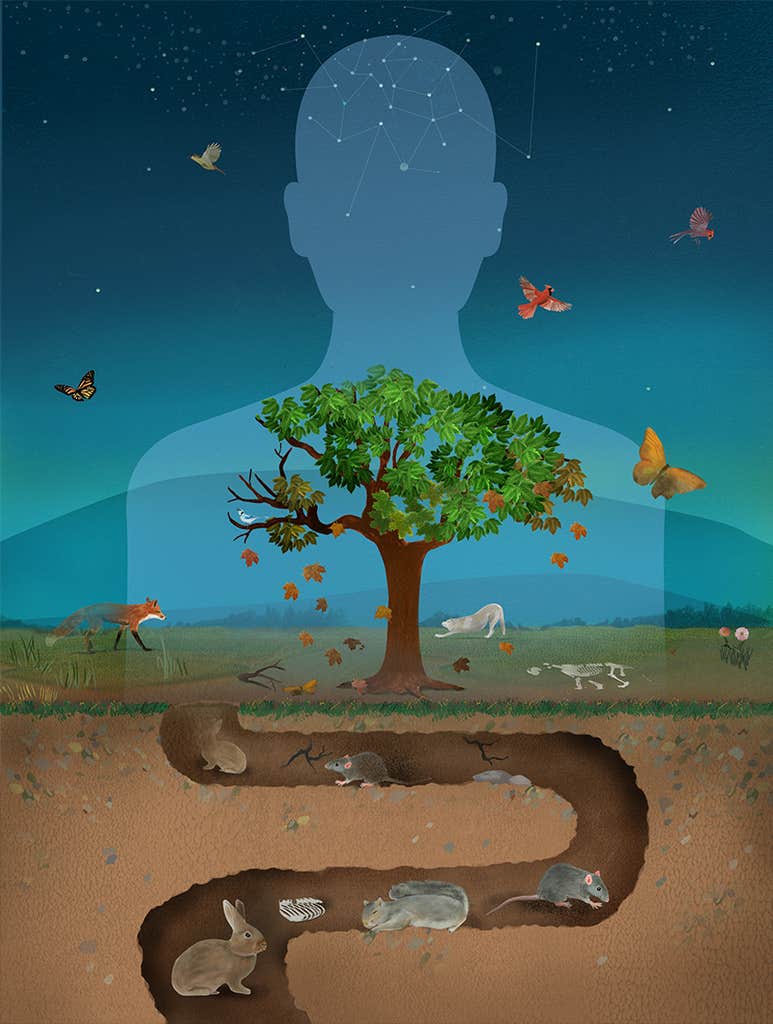

While Borjigin acknowledges that her work is preliminary, her observations and others like them show just how blurry the line between life and death has become, and how much science still stands to learn about such a pivotal event. As technological advances increasingly allow researchers to study death—including interventions that now allow for the use of so-called living cadavers in scientific research—so too have they necessitated new, oftentimes fraught conversations about the nature of death, its biological and societal underpinnings, and whether existing legal definitions are in alignment with current medical standards.

“The somewhat contentious space that we’re in right now is that we have different ways that we can say that someone is dead, and not all of them agree with each other. There are legal definitions and medical ones, social definitions, and many different religious interpretations,” says L. Syd M. Johnson, a neuroethicist at SUNY Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. “It’s a surprisingly complicated question, but that also makes this an exciting time to be considering it.”

Across many cultures, life has been linked not to our bodies, but to intangible souls, and so questions of death remained most squarely in the purview of religious representatives. Early definitions associated with Western religions in the mid 1700s timestamped death using the soul’s departure from the body. It wasn’t until about a century later that the first biological description of death—the cessation of heart action and breathing—appeared in a medical text, 1873’s Manual of Medical Jurisprudence, written by Alfred Swaine Taylor, a British toxicologist and medical writer. This so-called cardiopulmonary concept dominated scientific thinking for the next century, and remains the most common criteria by which doctors declare someone dead today.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience.

Log in

or

Join now

.

But medical advances, including interventions such as CPR and organ transplantation and the emergence of technologies including ventilators and defibrillators, have increasingly clouded that definition. People who might once have died from drowning or heart failure can now be resuscitated, receive an organ transplant, or even have their circulation artificially maintained. Death, many scientists now argue, is better thought of not as an absolute, but as a complex and evolving process that can sometimes be reversed with proper care.

“Irreversibility is just a reflection of a lack of medical treatments, which we’re developing more of all the time,” says Sam Parnia, a clinician at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City who focuses on cardiac arrest. “We see now that death is a continuum, and cadavers are often in a state of reversibility for hours, if not days postmortem.”

The emergence of neuroscience as a discipline prompted even more rethinking on death. In 1968, a committee based at Harvard University met to establish a definition centered around neurological criteria. In their final report, the group described death, in part, as an “irreversible coma,” a term they used somewhat interchangeably with what we would today refer to as brain death.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience.

Log in

or

Join now

.

Not everyone agreed with this approach, with one researcher calling the recommendations “a bane for bioethicists from day one.” At the time, the question of when to stop providing life support was not clearly differentiated from the question of when a patient was dead, and the group’s chair, Harvard anesthesiologist Henry Beecher, referenced a hypothetical future in which “hopelessly unconscious” patients would take up space in hospitals at enormous cost. Others were hesitant to declare death too soon, however, worried that premature declarations could be rushed to kickstart the harvesting of organs for donation.

Some of this contention was settled with the passing of the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) in 1981, a model United States law intended to help states craft their own unified policies. The UDDA sought to bridge the cardiopulmonary and brain-based concepts, defining death as either the irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem. This latter point acknowledges that it’s the brainstem that controls essential, automatic functions such as breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure, and its inclusion places the UDDA more in line with a “whole-brain” approach rather than a “higher brain” model focusing on consciousness as a hallmark of life. Today, medical professionals use UDDA criteria when declaring someone dead, kickstarting the legal, social, and clinical processes that come next, including organ donation, mourning rituals, and the settling of a person’s personal affairs.

The UDDA has generally been successful in its purpose for the past 40 years, says David Magnus, the director of the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics in California, even though it too has garnered its share of controversy. “The UDDA is an amazingly successful policy—tens of millions of people die each year, and we’re generally not arguing over that because of the criteria we have,” he says. “Having said that, a feeling has grown over time that there’s a lack of fit between the actual language of the law and the details of clinical practice, such that we’re now reconsidering our definitions once again.”

Many of the arguments around how we define death stem from a lack of consensus over what tests or metrics should be used to verify that death has occurred, and how much philosophy should factor