From skating to curling, the thrilling sports of the Winter Olympics have plenty of science behind them. Follow our coverage here to learn more.

For at least a decade, the quadruple axel jump was figure skating’s white whale. “It’s been this unreachable thing, like the four-minute mile” once was, says Matthew Lind, a technical specialist for U.S. Figure Skating. Throughout the 2010s male skaters kept landing new jumps that rotate four times in the air: the lutz, the loop, the flip. But at 4.5 rotations, the quad axel is a special case, and it remained incredibly risky to attempt, let alone to perfect.

Then came Ilia Malinin. In a video on the U.S. skater’s Instagram, he lands two in a row with only a split second between them, like it’s nothing. He became the first—and still, the only—skater to land the quad axel in competition in 2022. He calls himself the Quad God, and it’s hard to disagree with him.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“He’s a phenom,” says figure skating coach and former Olympian Karen Preston. His jumps “are pretty darn close to perfect.”

Malinin represents the direction in which figure skating has been moving for at least 20 years, rewarding harder and flashier jumps. I spoke with figure skating coaches and biomechanics researchers to learn how these jumps became possible, what makes Malinin special, and whether we’re headed toward the era of quintuples.

Pushing Boundaries of Physics

From a physics perspective, the six main jumps of figure skating are variations on the same theme. Skaters glide along the ice to build momentum, then twist themselves up like springs and push off with explosive muscle movements. They have two goals: to jump high to maximize their time in the air and to rotate fast to complete the turns before their foot comes slamming back to the ice. During takeoff, skaters push off the ice at an angle, which lets them maximize angular momentum, or the ability to rotate quickly.

Each jump accomplishes this differently. The axel is the only jump in which skaters take off while facing forward, which is part of what makes it so difficult—because it is landed backward, skaters must rotate an extra half turn before they land. The five other jumps take off backward and can be launched from the figure skate blade’s distinctive toe pick or from either of its two edges.

Amanda Montañez

Though the jumps may be similar physics-wise, for the human body, every jump is different. And they only get harder with more rotations, requiring skaters to propel higher and rotate faster. The margin for error becomes slim. “You’re really putting your body at risk,” Lind says. For elite skaters, landing these harder jumps requires strength and conditioning, innate talent, mental focus, great coaches—and a slight body, explains biomechanics researcher Lee Cabell, who coaches figure skating at IceWorks Skating Club in Pennsylvania.

The importance of a narrow body comes down to physics. Because angular momentum must be conserved, skaters can’t change their rotation potential once they’re in the air. But they can change their spinning speed by pulling their arms close to their body. This movement brings more of the skater’s mass closer to their axis of rotation, decreasing what’s called their moment of inertia and increasing the speed of their rotation by making it require less force.

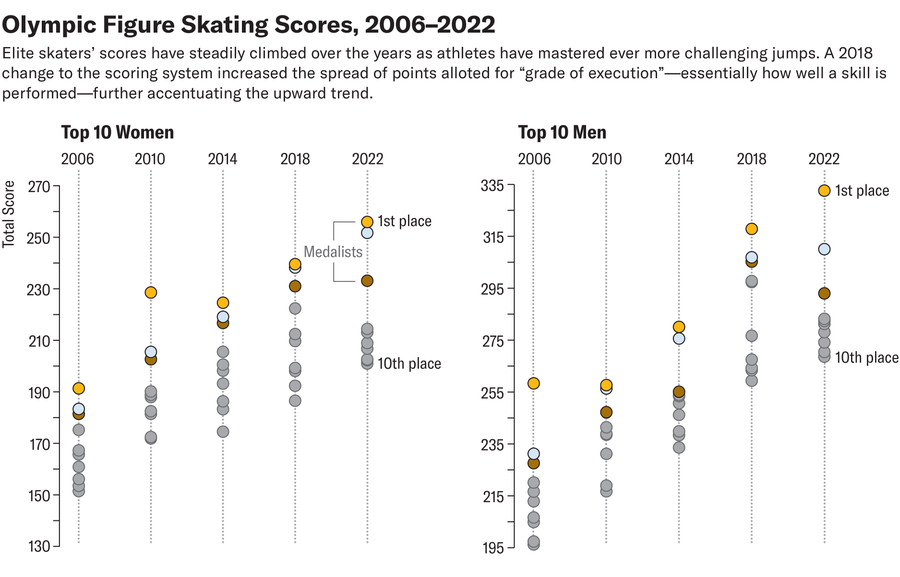

Narrower bodies, then, have the capacity to spin faster. “These very slight but muscular athletes really have the advantage for rotating,” says Sarah T. Ridge, a biomechanics researcher at the University of Hartford, who studies figure skating. With his slight body, immense talent, and parents who are former Olympians and double as his coaches, Malinin is a rare skater with the whole package, Cabell says. Another outlier is Nathan Chen, who landed five quads in one program at the 2022 Olympics and took home the gold. Both have dominated the sport, with scores far above the rest of the pack.

Amanda Montañez; Source: skakingscores.com (data)

For a while, it seemed like quads were taking over women’s skating, too. In the early 2020s the field was dominated by young, predominantly Russian teenagers who could land quads, a feat that is easier in narrower, prepubescent bodies. But after one of these young skaters was caught up in a doping scandal at the 2022 Olympics, the International Skating Union (ISU) raised the minimum age to compete to 17. Now the quad’s relevance in women’s skating has faded. All eyes there are on the triple axel, an element that was once very risky but which skaters are