The sharpest criticisms of the book Abundance have sometimes come from the antitrust movement. This group, mostly on the left, insists that the biggest problems in America typically come from monopolies and the corruption of big business.

In housing, for example, Ezra Klein and I write that a key bottleneck to homebuilding in the last few decades has been legal barriers to construction, including zoning laws and minimum lot sizes. This is a mainstream view supported by economists and scholars who have studied the issue for decades. The antitrust left, however, claims that the more significant factor is that big homebuilders abuse their power by holding back construction to juice their profits. “Big homebuilders withhold housing supply,” the antitrust advocate Matt Stoller has claimed. In their paper “Post-Neoliberal Housing Policy,” the law professors Christopher Serkin and Ganesh Sitaraman criticize market concentration in homebuilding and call for “tools from anti-monopoly policy.”

At a high level, I have never found these arguments persuasive. One hallmark of a monopolistic market is rising profits. But researchers have found that developer profits have remained steady. According to the National Association of Home Builders, profit margins as a share of overall home-sale prices actually declined slightly between 2002 and 2024.

Still, I wanted to spend more time engaging with the arguments of the antitrust housing folks. One of the most detailed articles in this space is an analysis of the Dallas, Texas, housing market by the lawyer and writer Basel Musharbash. In “Messing With Texas: How Big Homebuilders and Private Equity Made American Cities Unaffordable,” Musharbash writes that housing in the Dallas metro, like many other cities, has become much more expensive in the last few years. He also points out that homebuilders in Dallas, as in many other cities, have gotten bigger in the last few years. Musharbash claims that these things are connected: Large builders are crushing competition and restricting supply to sell houses at monopoly margins. To restore affordability, he says, policymakers should “dislodge the powerful corporations” that build America’s homes.

I’m not an economist or a lawyer. I’m just a journalist. To the extent that I’m good at anything, it’s calling people on the phone and writing down what they say. So I reached out to the primary sources that Musharbash quotes throughout the piece.

What I found was astonishing. The economist Musharbash cites told me that his theories had been misapplied. The housing analysts quoted in the piece told me Musharbash distorted their points and reached dubious, or even flatly wrong, conclusions. The leading monopoly researcher I spoke to, whose work has been celebrated by the antitrust left, told me that the entire thrust of the article—and, by extension, much of the antitrust-housing philosophy—defied sophisticated antitrust analysis.

The essay you’re reading is very long. But I can sum it up in one sentence: The Musharbash essay on Dallas—like too much of the antitrust left’s work on housing—is filled with out-of-context quotes, overconfident assertions lacking evidence, and generally misguided claims. Now let’s go through them one by one.

Claim #1: Dallas is a “homebuilder oligopoly.”

Reality: I called the key oligopoly researcher cited in the Musharbash essay. He disagreed with the use of his work and told me that any city with Dallas’s construction record was “100 percent” not an oligopoly.

It is a fact that home prices across the country have increased in the last decade. It is also a fact that homebuilders have gotten bigger in the last few years. The question at stake here is: Is the second fact causing the first fact?

I believe there is only one economic paper that unambiguously says yes. It is a 2023 working paper entitled “Fewer players, fewer homes: concentration and the new dynamics of housing supply” by the economist Luis Quintero. This research is load-bearing in the antitrust world. It’s quoted in articles and social media posts by the antitrust advocate Matt Stoller. You’ll find it in research from other antitrust scholars. And it seems to be the only empirical research in Musharbash’s essay.

I called Luis Quintero to ask what level of market concentration in homebuilding he considered to be dangerous. In the most concentrated markets, Quintero said, one or two firms account for 90 percent of new housing. But problems begin to accelerate, he said, if five or six firms account for 90 percent of new housing.

I immediately saw a problem. In Dallas, the top two firms built just 30 percent of new homes in 2023. The top six firms barely account for 50 percent of new housing. Musharbash’s claim that a homebuilding oligopoly is crushing housing supply in Dallas relies on an economic analysis that doesn’t apply to Dallas at all. I asked Quintero about this: Would you agree that Dallas is “a bad application” of your paper? “I would definitely agree,” Quintero told me.

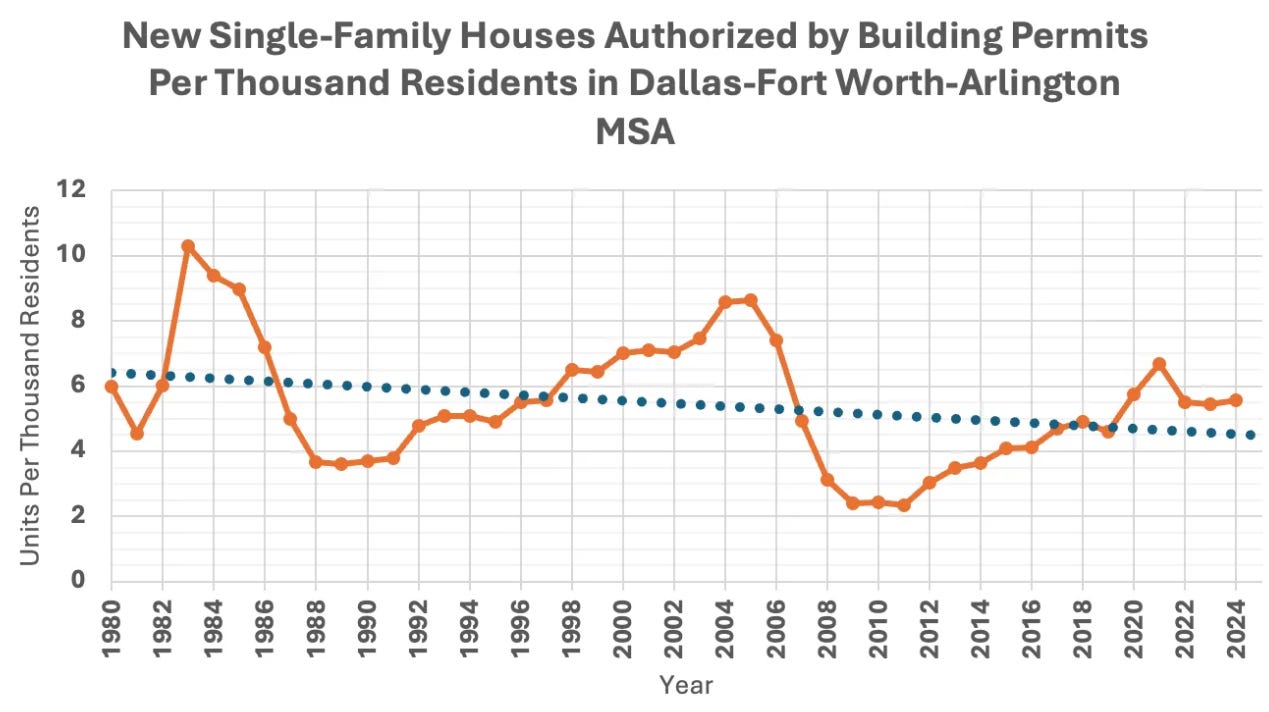

It gets worse. By Musharbash’s own calculation, the number of new single-family houses permitted per capita in the Dallas metro area rose steadily between 2010 and 2022. (This is illustrated in the graph below.) I mentioned to Quintero that steadily rising construction per capita in a fast-growing city seemed like a weird example of monopolistic abuse. “One hundred percent,” Quintero said. “I 100 percent agree that in places where construction per capita is increasing like that, it’s very unlikely that [a dangerous level of] concentration is growing.”

So, Dallas doesn’t meet Quintero’s oligopoly threshold. Now let’s consider the rest of the country. I tracked down a complete listing of the country’s 50 largest homebuilding markets, from #1 Dallas to #50 Cincinnati. How many meet Quintero’s first oligopoly threshold (two companies = 90 percent of the market)? Zero out of 50. And how many meet his second threshold (six companies = 90 percent of the market)? One: Cincinnati. It turns out that the largest homebuilding markets just aren’t that concentrated, even when you accept the yardstick of the economist who’s offered the only empirical definition of market concentration in homebuilding that I can find.

To put it starkly: Musharbash’s essay relies on the work of an economist who told me his theory is being “100 percent” misapplied to Dallas; and the antitrust folks alleging a national homebuilding oligopoly are pointing to an economic definition of oligopoly that doesn’t apply to the 49 largest metros in the country.

Brief interlude: What does Luis Quintero’s working paper actually say, and are its findings plausible?

Quintero’s working paper plays such a foundational role in the antitrust housing landscape that I think it’s important to briefly address what it says and why I’m a bit skeptical of its findings.

Quintero looked at hundreds of markets along the East Coast between Virginia and New York between 2006 and 2015. He found that as dominant homebuilders increased their market share, new home production fell. “If you take two places with similar demand, and one place has fewer developers, that place is going to have less production per developer,” he said. From this study sample, Quintero calculated that the rise in market concentration in homebuilding is so severe that it has reduced the annual value of housing production nationwide by $106 billion a year.

After a long and polite conversation with Quintero on the phone, I came away with two concerns about his paper.

First, he uses 2006 as his baseline. This was a highly atypical year in housing. Just before the housing crash that triggered the Great Recession, May 2006 was the peak of 21st century construction employment. That very month was construction’s single highest share of total employment since the postwar era. Using a bubble year as a baseline could easily throw off the overall findings of any economic analysis.

Second, as I told Quintero on the phone, I don’t think it’s plausible that oligopoly in homebuilding is destroying $100 billion in production every year if only one of the 50 largest homebuilding markets meets his red line of oligopoly. Quintero offered a defense of this discrepancy. He suggested that the most concentrated homebuilding markets tend to be either suburbs outside of major metros or small towns, since these are places “where new homes are a higher share of overall homes.” I can absolutely believe that. But I don’t see the value in discussing a “national” crisis in homebuilding oligopoly from which the 49 biggest metros are exempt.

Claim #2: Dallas housing experts say local homebuilders are monopolies who are “devouring” the market.

Reality: When I called up a Dallas housing expert cited several times in Musharbash’s essay, he disagreed profoundly with its thesis. He’s actually a big YIMBY.

Musharbash claims that Dallas homebuilders “undermine free and fair competition” by acting as monopolies. To make the case, he leans heavily on the work of John McManus, a housing analyst who is also the founder and editor-in-chief of the real estate site The Builder’s Daily. Musharbash writes:

“Described as “unstoppable, market-share-devouring juggernauts” by Builder’s Daily magazine [sic; should be The Builder’s Daily] these dominant incumbents appear to deploy their power to undermine free and fair competition …

Indeed, “[t]he scale and sway of market leaders” — particularly D.R. Horton and Lennar — means they “often monopolize access to trades and vendor resources” in local markets, constraining the ability of smaller builders to build at all, according to Builders Daily [sic, again]

I called McManus to ask if he really thought Dallas homebuilders were monopolies deforming the local housing market and driving up prices. “No,” he said. “I don’t think the price increases in Dallas have much to do with big companies at all. I’ve read that commentary, and I disagree with it. I don’t think the big builders have a strategy to sell fewer but more expensive homes.”

So, what did McManus think was more responsible for driving up the cost of housing in Dallas? “Land use regulation,” he said. “Zoning?” I asked. “Yes. Land constraints and zoning that require certain footage along the street, or minimum lot sizes, or requirements about three-car garages, are more the cause of the prices increasing now,” he said. “Municipalities have been adding more of [these rules] in the last few years, and land use constraints have become more meaningful because the new parcels that have come online are subject to stiffer restraints.” Beyond raising overall prices, McManus said, these rules specifically thwart the con