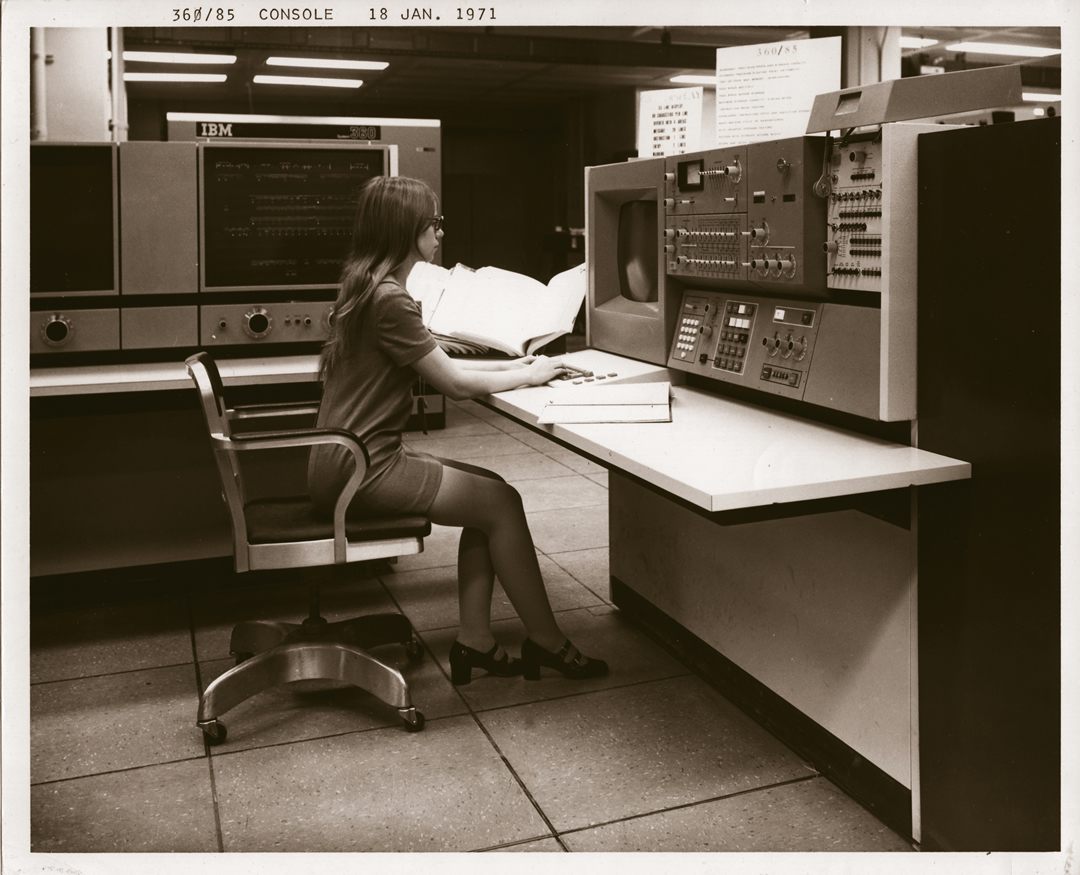

A federalgovernment representative utilizes an NSA IBM 360/85 console in 1971 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons/NSA).

It’s been a odd week for America’s most important business—a company whose tech items have such customer goodwill they got away with forcing us to listen to U2—who is poised to go to court versus its own federalgovernment over its users’ right to personalprivacy. The federalgovernment is conjuringup an unknown law dating back nearly to the starting of the nation to force the business to comply. It’d be a quite great film.

But it’s simply the most significant flare-up in a prolonged fight inbetween federalgovernment authorities, cybersecurity specialists, and the tech market over how customer’s technical information is secured, and whether or not the federalgovernment has a right to gainaccessto that details.

In reality, the federalgovernment has really won this battle before—secretly.

Throughout 2015, U.S. politicalleaders and law enforcement authorities such as FBI director James Comey have openly lobbied for the insertion of cryptographic “backdoors” into softwareapplication and hardware to enable law enforcement firms to bypass authentication and gainaccessto a suspect’s information surreptitiously. Cybersecurity professionals have all condemned the concept, pointing out that such backdoors would basically weaken fileencryption and might madeuseof by badguys, amongst other concerns. While a legal required or public contract would be required to enable proof gotten through backdoors to be permissible in court, the NSA has long attempted—and sometimes prospered—in positioning backdoors for hidden activities.

An Enigma maker at Bletchley Park, long-rumored to be one of the veryfirst backdoored gadgets (Photo: Flickr/Adam Foster).

One of the most crucial advancements in cryptography was the Enigma device, notoriously utilized to encode Nazi interactions throughout World War II. For years, reports have continued that the NSA (then SSA) and their British equivalents in the Government Communications Headquarters teamedup with the Enigma’s producer, Crypto AG, to location backdoors into Enigma devices offered to specific nations after World War II. Crypto AG has consistently rejected the claims, and in 2015 the BBC sorted through 52,000 pages of declassified NSA files to discover the reality.

The examination exposed that while no backdoors were positioned in the makers, there was a “gentlemen’s arrangement” that Crypto AG would keep American and British intelligence evaluated of “the technical specs of various devices and which nations were purchasing which ones,” permitting experts to decrypt messages much more rapidly. Consider it a security “doggy-door.”

Next, in 1993, the NSA promoted “Clipper chips,” which were meant to safeguard personal interactions while still enabling law enforcement to gainaccessto them. In 1994, scientist Matt Blaze uncovered substantial vulnerabilities in the “key escrow” system that enabled law enforcement gainaccessto, basically making the chips worthless. By 1996, Clipper chips were defunct, as the tech market embraced more safeandsecure, open fileencryption requirements such as PGP.

In more current years, the NSA was unquestionably captured placing a backdoor into the Dual_EC_DRBG algorithm, a cryptographic algorithm that was expected to create random bit secrets for securing information. The algorithm, established in the early aughts, was promoted by the NSA and consistedof in NIST Special Publication 800-90, the authorities requirement for random-number generators relea