PHOTO BY ANGELA PETERSON/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

Published

Updated

PHOTO BY ANGELA PETERSON/MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL

On the morning of May 3, 2002, Alexis Patterson’s stepfather walked her to the corner and a crossing guard guided the 7-year-old across the street toward Hi-Mount Community School in Milwaukee. At the end of the day, she didn’t come home.

A month later and more than a thousand miles away, Elizabeth Smart, 14, went to sleep in her bedroom in Salt Lake City. By the next morning, she was gone.

Within hours, Elizabeth’s disappearance was featured on CNN’s “Larry King Live” and Fox News’ “On the Record with Greta Van Susteren.” It took eight days for Alexis’ story to attract attention outside Milwaukee, with a segment on “America’s Most Wanted.” The next national story on her case aired weeks later.

By the time Elizabeth had been gone two weeks, USA TODAY had published three stories about her disappearance. There were none focused on Alexis.

The law enforcement response also differed. The day after Elizabeth disappeared, police called in the FBI and offered a $250,000 reward. In Milwaukee, the FBI didn’t join Alexis’ case until three days after she vanished. Nineteen days after she was last seen, the sheriff’s office offered a $10,000 reward.

Elizabeth is white. She was found nine months after her abduction. Alexis is Black – and still missing.

Timeline: How the missing child cases of Alexis Patterson and Elizabeth Smart differ

Mark Hoffman, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Twenty years ago, as police searched for the two girls, some advocates and experts argued that race was a key factor in how authorities and reporters handled their cases. It marked the first time the national media paid serious attention to such disparities.

Two years later, Black journalist Gwen Ifill gave the phenomenon a name: “missing white woman syndrome.” She coined the term after the disappearance of Laci Peterson, a pregnant California woman whose husband was later convicted of killing her. It played out again in 2005, when Natalee Holloway vanished on a class trip to Aruba.

Over the past eight months, the case of Gabby Petito, who disappeared on a road trip with her fiance and was later found dead, has once again brought the issue to the forefront of the public consciousness.

The fact that missing Black people command less media attention than whites has been well documented by academic researchers. Their studies have repeatedly found that cases of missing Black people, children and adults alike, are covered less often than whites and their stories don’t travel as widely through the nation’s newsrooms.

There is little empirical evidence that explains why.

A leading theory faults the lack of racial diversity in newsrooms and media ownership. Another blames the socioeconomic status of Black victims. Because missing Black children often come from high-crime, low-income neighborhoods, the reasoning goes, their families have less influence with law enforcement and fewer financial resources to devote to publicity campaigns.

The way police categorize a disappearance also plays an important role. Cases of suspected abduction, like Elizabeth’s, garner more attention from cops and reporters than children considered runaways by police, as Alexis initially was.

Fred Hayes, WireImage

In new research yet to be published, Syracuse University Professor Carol Liebler found that law enforcement officers are the most prominent sources in 87% of news stories about missing children.

“My own thought is that police contribute to the problem by setting the news agenda through what cases they share with media,” she said in an email.

Smart, now an advocate for missing children, acknowledged after Petito’s disappearance how problematic it is that the cases of missing white people get more attention than missing people of color.

Smart, who was unavailable for an interview with USA TODAY while taking time away with her family, made the comments last year on the Facebook Live series Red Table Talk.

When I think of all of these other victims, I feel like they still deserve, just every bit as much, to be found.

“When I think of all of these other victims, I feel like they still deserve, just every bit as much, to be found,” she said. “I don’t think there’s anyone … who is any less worthy than anybody else, myself included, to come home.”

In the coming months, USA TODAY Network reporters will embark on a national project to compile data and public records that expose why these disparities in police response and news coverage of missing children occur and how they can be addressed. In addition to race, we will examine other factors that may explain the discrepancies, including families’ incomes, whether they live in urban or rural areas and whether they have had past contact with police.

We need your help. If you know of missing children of color in your community or have experienced these disparities firsthand as a parent, friend or law enforcement officer, we want to hear from you.

Based on your tips and our own research, reporters around the country will tell the stories of missing children who have yet to be found. Children like Alexis Patterson.

Help USA TODAY investigate disparities in missing children cases.

If you know of missing children of color in your community or have experienced these disparities firsthand as a parent, friend or law enforcement officer, we want to hear from you.

The distance from Hi-Mount Elementary to the Pattersons’ front door was just 242 steps. Alexis always got home from school around 2: 50 p.m. When she hadn’t arrived by 2: 55 on that Friday in May 2002, her mother, Ayanna Patterson, began to worry. At 3, Patterson ran to the school in a panic.

“That’s when I found out that my baby never made it,” Patterson told USA TODAY. “She never made it to school.”

None of the teachers had seen Alexis that day, but no one had notified her parents of her absence even though the straight-A student prided herself on perfect attendance. Patterson checked with her grandmother, who lived nearby, but she hadn’t seen the girl either.

So Patterson called the police.

Within a day, the Milwaukee Police Department set up a mobile command post, a trailer packed with communications equipment, at a park near Alexis’ home, according to news coverage at the time. Three days later, Milwaukee Police Chief Arthur Jones told reporters he believed Alexis had run away.

Erwin Gebhard

That theory stemmed from an argument she had with her mother the morning she disappeared. The previous day, Patterson had taken Alexis to the store, where she picked out some cupcakes to share with her classmates. In the morning, Patterson realized Alexis hadn’t finished her homework, so she wouldn’t let her bring the treats.

Despite investigators’ belief that Alexis was so angry she skipped school, Milwaukee police acted with extreme urgency, said Chief Jeffrey Norman, who was a detective back then.

“There was a frenzied approach of, ‘There’s someone missing in our community, a young one, and we’re going to put in all the effort, the work, hold no stops,’” he said in an interview last week. “I know that the department took it very seriously. We all paid attention. We were all expected to have some type of role.”

If Alexis went missing today, Norman said, police would issue an Amber Alert because of her age. The alerts, which are disseminated to the public and the press via cellphones, billboards, news organizations and social media, include children’s photos, descriptions and information about when and where they were last seen.

TOP: Student volunteers from El Puente High School in Milwaukee gather to hand out flyers and help in the 2002 search for Alexis Patterson. BOTTOM: A Milwaukee Police officer climbs out of a boarded up home on the 2100 block N. 33rd St. in Milwaukee during the search for Alexis.

LEFT: Student volunteers from El Puente High School in Milwaukee gather to hand out flyers and help in the 2002 search for Alexis Patterson. RIGHT: A Milwaukee Police officer climbs out of a boarded up home on the 2100 block N. 33rd St. in Milwaukee during the search for Alexis.

TOM LYNN, AP

A federal law designed to help states implement Amber Alerts nationwide was passed in 2003 – the year after Alexis and Elizabeth vanished – and all 50 states had set them up by 2005. As of the end of last year, more than 1,000 missing children had been recovered as a result of the alerts.

In 2002, Wisconsin had not yet adopted Amber Alerts. Although it was then called a Rachael Alert, Utah had already set up its system – another key difference between Alexis’ case and Elizabeth’s. As a result, information about Elizabeth’s abduction was disseminated widely within hours. The Deseret News ran a story the following day.

In Milwaukee, the first story about Alexis was published in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel on Sunday, two days after she disappeared.

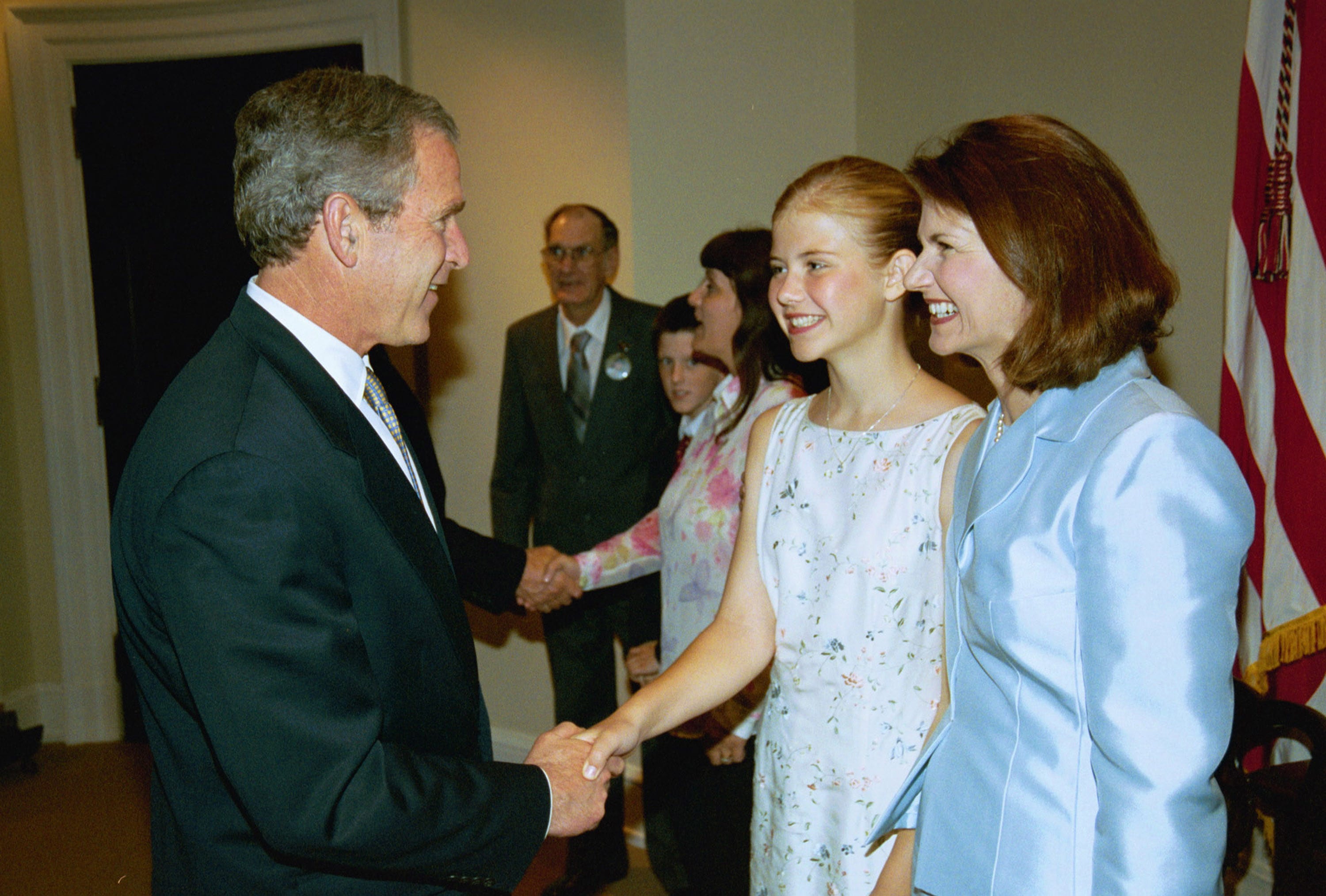

The White House, Getty Images

In any missing child case, it is standard procedure for police to start with those closest to the child, includ